Photo by Steve Rainwater, ca 1979, Canon A1 w/Canon 50mm f/1.4 lens

Robert E. Spaulding, Jr. or “Mr. Spaulding”, as I knew him when he was my high school math teacher, died on July 16 at the age of 82. I’ve been out of touch with him since my high school days, which is sad because I never got the chance to tell him what an impact he had on my life. Every student has that one teacher who made a difference and for me that was Mr. Spaulding. I tried to locate him a few times over the years but in pre-Internet days it was a bit harder to track someone down.

I heard about his passing from another high school friend. There’s not much online in the way of an obituary and I’m not sure if he has any surviving relatives or descendants. As interesting, eccentric, and meaningful to my own life as he was, I’d hate for him to be forgotten, so here are a few memories of him.

I came from a very religious family and, after attending a public elementary school, ended up at a private religious school. That school was First Baptist Academy, operated by the First Baptist Church in downtown Dallas. It was a conservative, evangelical church back then under W. A Criswell. In retrospect, he seems mild compared to the modern head of the church – the notorious Robert Jeffress, who is more of a right-wing political operative, Fox news personality, and wack-a-doodle Trump apologist than any sort of real religious figure. So I suspect I really didn’t have it too bad compared to current students.

There were good teachers and bad teachers in high school. Most that I remember were above average. One stood out immediately as unique: Mr Spaulding, a math teacher. He looked different with his pocket protector filled with more pens and pencils that he could possibly need. He always had several calculators on his person including in belt holsters. He carried a strange, boxy brief case with giant metal hinges that looked like it came from another century. He frequently had a can of Dr. Pepper nearby. Unlike the other teachers who used white chalk, he had boxes of colored chalk and used every color they contained.

And Mr. Spaulding didn’t just look different. He had all sorts of fascinatingly eccentric habits. For example, his multi-colored chalk board work, in addition to equations and graphs, frequently included doodles of a math teacher in a cape he referred to as “super teacher”.

Photo by Steve Rainwater, ca 1979, Canon A1 w/Canon 50mm f/1.4 lens

He sometimes complained about the temperature in his classroom and the official rules for the building’s thermostat. Air vents in that old, downtown Dallas building could not be throttled or closed. But he invented his own solution. When too much cold air was blowing in, he would begin inflating balloons one-by-one and stuffing them up into the large circular vent above his desk until the duct work was so full of balloons that no air came out.

When a student misbehaved, he didn’t yell, he would simple “Zot” the offending student. A zot consisted of a hand movement reminiscent of a Greek God preparing to emit a lightning bolt combined with him speaking the word “zot”. I think first-time students may have shut up and behaved simply because they were so confused by what had just happened. (side note: some quick googling suggests zot may have originated with the 1958 newspaper comic strip, B.C., in which it was the printed sound-effect accompanying a lighting bolt strike on one of the characters.)

When a student said “When will we ever use this in real life?”, he was good at finding examples that appealed to the student who asked. In answer to one student who asked the question, he used the student’s interest in all things military to propose a scenario in which said student is piloting a futuristic aircraft, carrying a nuclear bomb with which he has to destroy an enemy stronghold. If he fails, a counter-attack will destroy the western world. His plane has taken some hits, and he’s flying with no computers, just instruments. To get out alive he has to achieve a minimum safe distance from the nuke after dropping it. He needs to fly in low under the radar, pull up at the last minute, drop the bomb while accelerating straight up, and reach a safe altitude before the bomb arcs back towards the ground and detonates. With the computer down he has to do the math in his head.

Turns out saving the world depends on whether he paid attention in Mr. Spaulding’s class that day because the seemingly useless math he was teaching was exactly the math needed to solve the problem. I recall him spending almost the entire class setting up the example with his usual multi-colored diagrams. A lot of students were bored out of their minds that day but to the one who asked the question, it was the coolest thing ever and probably the first time he’d actually enjoyed a math class. As I watched the whole thing unfold, it was the first time I’d seen a teacher put that much into getting through to one student before.

On another occasion, when several jocks were not understanding the math, he re-oriented the curriculum on the spot, basing it around a new problem that involved the body weight and running speed of football players. There was a football game coming up that evening and he got them involved by asking them to give numbers for players on our school’s team and compared them to numbers they estimated for players on the opposing team. I doubt any of them became math majors but it was the only time I recall seeing them participate in a math class with any interest.

In my own case, I had developed a bad habit of doodling little space ships in the margins of test papers. A lot my teachers just ignored it but Mr. Spaulding alternated between one of two responses. I occasionally got my test back to find “-3 for space doodles” but more often, I’d get my test back to find little biplanes, drawn with a red grading pen, shooting at my space ships.

I was an avid reader of science fiction and almost always had a paperback book by Asimov or Bradbury with me in those years. Mr. Spaulding was a fan himself. I would occasionally sneak out of the sportsball pep rallies that students were supposed to attend, and sometimes ended up in Spaulding’s classroom talking about science fiction ideas or just sitting and reading.

Then there were days when you’d come to Mr Spaulding’s class and find out he was not in the mood to teach any math that day. He was going to teach something but it wasn’t math. He had ideas on subjects ranging from politics to theology. He often illustrated a point by way of telling one of many stories about his days stationed on a top secret US nuclear missile launch site in South Korea. At the time, there was debate among the students as to whether those stories were real or completely made up. None of us had ever heard about nuclear missile launch sites in South Korea and it seemed far-fetched.

I only recall a couple of his Korean stories. One involved a big tough soldier who claimed the missile engineers were all wimps and spent most of his time lifting weights outside near the launch pads and talking about how he’d probably have to save them all if things got serious. One day they got a high level alert with launch codes and came with seconds of a launch. The engineers were all busy doing their thing while the tough guy sat by his weights crying for his mother because he thought they were all about to die.

Another story involved missile maintenance and I think may have been used to illustrate a math or physics point. He said they periodically had to pull the gyroscopes out of the missiles for testing and maintenance. The gyroscopes were able to briefly generate hundreds of pounds of force (from the description I’m guessing early CMG devices used for attitude control in the missles? Not sure what other gyroscopic component in an old missile could do something like this?). One of the missile engineers devised a portable power supply that would allow them to put the gyroscope assembly inside of a large suitcase. They added a hidden switch to handle. They then drove to a nearby hotel, got out of the car and carried the suitcase up to the bell boy at the door. As they set it down, they secretly activated the gyroscope, then asked the bell boy to carry it in for them. The suitcase now effectively weighed a couple of hundred pounds and the bewildered bell boy couldn’t lift it. They’d ask what was wrong, reaching down to pick it up themselves, turning off the switch, and lifting it easily.

Many years later I read there actually were secret US nuclear missile bases in South Korean during the cold war. So who knows?

Other times he talked about theology. He also taught one of the school’s Bible classes. The interesting thing about his theology is that he seemed to think you could read the bible and figure out what it meant on your own. And he wanted to apply reason and logic to it. If you asked him a religious question, he could tell you the doctrine of every denomination and sect on the subject and explain why he thought most of them were wrong. Unfortunately, this meant that the administration of the school, who seemed to prefer “official” First Baptist Church theology, frequently were at odds with Mr. Spaulding’s ideas. But to any rebellious high school kid, religious or not, that made hearing Mr. Spaulding way more interesting than the official answers the other teachers gave.

I was only just beginning to emerge from my shell of strictly controlled religious doctrines and was fascinated by the idea that you could figure this stuff out for yourself, and that you could apply logic and reason to religion just like you did everywhere else. If an idea didn’t stand up to reason, you didn’t abandon reason and “take it on faith”, you discarded the idea. I suspect I’ve discarded more of my religion than Mr. Spaulding anticipated but he was one of several crucial influences that set me on the path to thinking for myself.

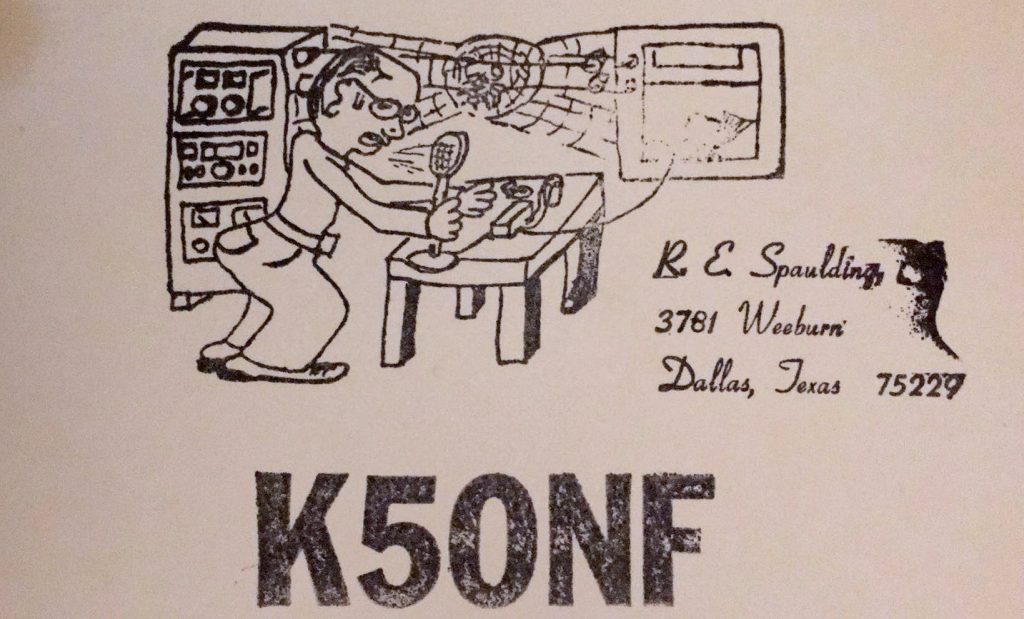

Mr. Spaulding was a Ham radio operator, electronics hobbyist, and seemed to know a little about everything. I and some of my friends dabbled in electronics too and this gave us someone to go to for advice when we ran into problems with our projects. We also once solicited advice from him on a model rocketry problem. We were trying to determine what altitude our rockets were reaching. We thought we could solve this as a trigonometry problem because it seemed like the observer, the rocket at apogee, and the launch pad formed a triangle. We described the problem to Mr. Spaulding one day and ended up learning trigonometry a little ahead of schedule.

I visited Mr. Spaulding and his wife at their home a few times. (I have a photo of it because I had just gotten my first real camera and was taking photos of everything that year). He had an entire room devoted to all his hobbies and projects. Besides all the radio gear, there were scopes and other test equipment and a workbench full of electronic stuff. One of the few projects I remember is a pair of glasses he was developing for blind people that converted light into sound. You put on the glasses, inserted some earphones and as you “looked” around the room, you heard variable tones that formed a sort of sonic image of whatever was in front of you.

Photo by Steve Rainwater, ca 1978, Canon A1 w/Canon 50mm f/1.4 lens

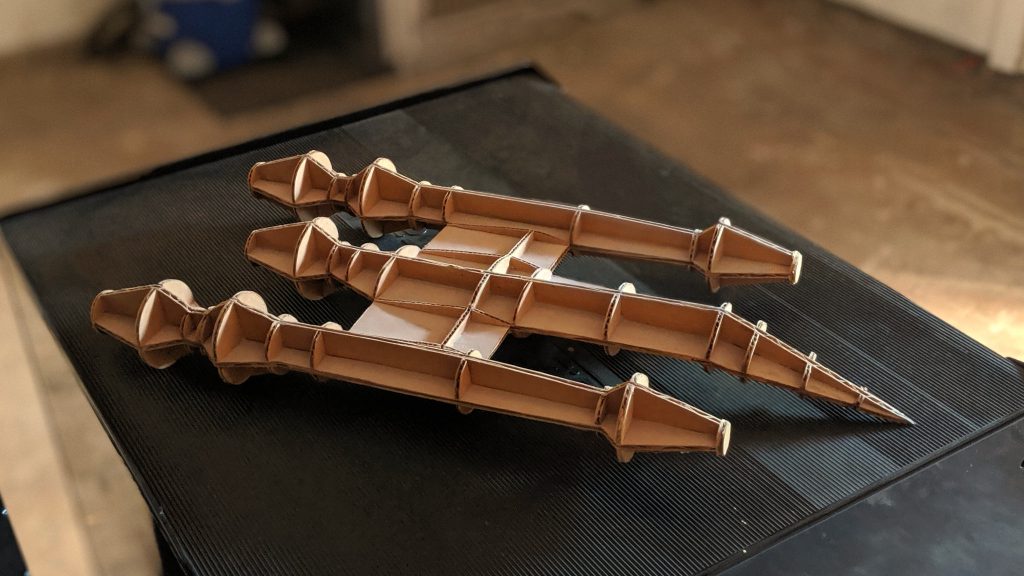

Another project he worked on for years was an ion-propulsion space craft design. He had models of various sizes in his home and he occasionally drew diagrams for us on the board at school, talking about how it would work. On one visit to his home, he gave me one of the models that had been superceded by a newer design. Believe it or not, I still have that cardboard spaceship model in a closet and it’s still in remarkably good shape. The ship has two propulsion nacelles, each with a circular particle accelerator fore and aft (the bulges near the tips). The double aft accelerators would provide forward thrust and the single fore accelerator braking thrust to slow down without needing to turn the ship around.

All good things come to end though and Mr. Spaulding retired from teaching near the end of my high school days, I believe at the end of my junior year. We got the impression it wasn’t an entirely voluntary retirement. He liked teaching but his theological ideas and his use of a slightly different translation of the Bible from the one preferred by the administration were creating lots of conflict. Earlier that year he stopped teaching any Bible classes but continued teaching math and science. He seemed increasingly frustrated that last year and the last time we talked after class on the last day of the school year he drew a final piece of chalk board art. I had my camera with me and captured it. He said it represented First Baptist Church crushing super teacher under the boots of their orthodoxy. You can just make out the blue-caped, fictional educator beneath the boot.

Photo by Steve Rainwater, ca 1980, Canon A1 w/Canon 50mm f/1.4 lens

I’m sure my memories barely scratch the surface. If you had Mr. Spaulding as a teacher and have any memories you’d like share, leave them in a comment below.