In the 1897 issues of Pearson’s Weekly there appeared a serialized story by H. G. Wells. It concerned a scientist who had developed and tested on himself a method of altering the refractive index of the human body so that it neither reflected nor absorbed light. That same year, the complete story was published in novel form as The Invisible Man. Not as fondly remembered as The Time Machine nor as far-reaching a story as Things to Come. It was, however, the first of many science fiction stories to bear a title of the form /The \w+ Man/. At least, that’s how you’d put in PERL regular expression syntax. If you prefer grep, then it would be ‘The [a-zA-Z]+ Man’. However you like your regular expressions, it’s a title that begins with “The”, ends with “Man”, and has a single word in between, usually a compound, interesting, and somewhat technical adjective.

My first literary encounter with this title form was a short story called The Non-statistical Man (1968, Raymond F. Jones), the story of a statistical analyst who gets a firsthand experience of the powers of intuition. Later, I ran across Isaac Asimov’s Hugo and Nebula winning The Bicentennial Man (1976), a short story about a positronic robot’s 200 year journey to be accepted as an equal in human society. I recently read the misogynist and so-bad-it’s-fun novel, The Reassembled Man (1964, Herbert D. Kastle) in which a sexist jerk is kidnapped by aliens and agrees to having his body disassembled for research purposes provided the aliens will reassemble him according to his ideals of the perfect man. Stephen King wrote a novel called The Running Man (1982, as Richard Bachman) which was turned into an Arnold Schwartzenegger movie a few years later. I’ve not read the original story yet but the movie is about a wrongly convicted and imprisoned man who escapes prison only to be recaptured and sentenced to die on reality TV.

That exhausts the stories I’ve read but there are still more I’ve only heard about. I recently managed to locate and purchase a copy of the long out of print Colin Kapp novel, The Transfinite Man (1964) and I’ve just started reading it. Philip K. Dick wrote the reasonably well-known novel, The Unteleported Man (1964) and also published a much earlier novella called The Variable Man (1953). Both are on my reading list.

There’s something I find appealing about that adjective in the middle of the title, especially when it includes an unexpected prefix like un- or dis- (e.g. unteleported or disassembled). Think of all the interesting prefixes that have become common in the last couple of decades thanks to science and technology. There’s the entire range of Si unit prefixes like pico-, nano-, tera- etc., common scienctific prefixes like omni-, contra-, hyper-. It seems like an inexhaustible supply.

While writing this, I noted with interest that three of the above books were published in the same year: 1964. Maybe there was a fad among authors or publishers for using this title format during the early 1960s? The last usage I could find was Stephen King’s The Running Man over 30 years ago. I think we’re overdue for a resurgence of this form. My question for anyone reading this is, what other stories, science fiction or otherwise have been published with this title configuration. I’m willing to be flexible enough to include other genres besides science fiction, so anything from comic books to journal articles are fair game.

While it’s not exactly what I’m after, I’d even be curious to hear close but slighly different title formats such as The Man Who Folded Himself by David Gerrold or The Woman Who Would Not Die by Carolyn Busey Bauman), though I think that form is likely to be much more common.

Update: How about some mini-reviews of the ones I’ve read so far? (in order of publication date)

The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells

The Invisible Man by H. G. Wells, 1897. A mysterious stranger, named Griffin, arrives in a small town. He wears a coat, hat, glasses, gloves, and covers his face with a scarf or bandages at all times. When the villagers get suspicious of his activities, he reveals that he’s invisible and goes on a rampage through the country side. His back story is slowly revealed and we learn that he was a psychopathic scientist obsessed with perfecting a method of making living creatures invisible. He develops a system that involves special drugs and exposure to radiation. After testing it on himself his equipment is destroyed. His secret is stored in three notebooks written in code. Griffin is set on becoming the ruler of the land, starting with this one tiny village but a fellow scientist, Kemp, is on to his plan. Kemp assists the local authorities in defending against Griffin’s attacks. It’s a short book and one of the classics so definitely recommended.

The Thin Man by Dashiell Hammett

The Thin Man by Dashiell Hammett, 1933, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., Vintage Books 1972 edition with cover art showing a photograph of Dashiell Hammett dressed as the thin man. This book stands out on this list as one of the few that isn’t from the genre of science fiction. But the name fits and I thought it would be fun to read. The Thin Man is a Hammett’s most well-known mystery novel and has been adapted into a series of movies, a Broadway musical, stage plays, a radio series, and a television series. In case you aren’t familiar with it, the story revolves around Nick and Nora Charles. Nick is a retired detective who is compelled against his will to solve a high-profile murder mystery when the couple visits New York City. The story involves crime solving, large quantities of alcohol, witty one-liners, and a large assortment of suspicious characters. The novel and the 1934 film are both recommended.

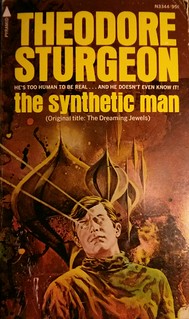

The Synthetic Man, by Theodore Sturgeon, 1950. Pyramid Books 6th edition, printed in 1974 with cover art by Gray Morrow. An orphan named Horty is adopted, along with a mysterious jack-in-the-box named Junky, by abusive parents. Junky’s eyes are crystals that hold an unexplainable importance for Horty. After a particularly bad bout of abuse, Horty takes Junky and runs away from home. A passing truck gives him a lift out of town. In the truck are some unusual people who inhabit the freak show of a traveling carnival. They befriend Horty and give him a new home in the carnival. His meeting may not be coincidence. Zena the dwarf seems to know something about Junky’s crystals. The carnival is run by Pierre Monetre, a doctor who uses it as an excuse to move around the country searching for crystals like Junky’s. He performs experiments on those he finds. Zena seeks to protect Horty from Monetre, who she believes is evil. Everyone in the carnival has something to hide and Horty believes someone is hiding the truth about his origin. When Monetre discovers Horty’s connection to the crystals, the entire human race may be in danger. Sturgeon is a good writer and the book is still quite enjoyable despite a few dated aspects of the story. Recommended.

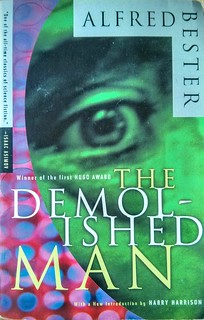

The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester, 1951, Galaxy Publishing Corporation. While there are definitely other good and enjoyable books on this list, The Demolished Man is the only one (so far) that’s widely recognized as a classic. This book is not only the winner of a Hugo, but the winner of the first Hugo ever awarded. Bester’s compact novels have a concise literary style that not everyone likes. His writing is the opposite of the verbose style of modern authors like Stephen King or Neal Stephenson. But the book is good and well worth a reading. The plot is reminiscent of the old detective show, Columbo. We start out knowing that brilliant and wealthy businessman Ben Reich is going to commit a murder. After the murder, law enforcement officer Lincoln Powell knows that Reich committed the murder. What’s different is that we’re dealing with a society in which murder never happens because benevolent telepaths have made crime an outdated and impractical idea. Powell knows Reich did it, because Powell is himself a powerful telepath. But telepathy is not acceptable as evidence in court and Reich has contrived what seems to be the perfect method of committing a crime without a trace of evidence. So the mystery is not who committed the crime but how Powell can bring Reich to justice, so that he will be found guilty in court and face the only acceptable punishment – demolition. Exactly what is entailed in being “demolished” is a mystery that is only slowly revealed. Recommended.

The Counterfeit Man by Alan E. Nourse, 1952, Thrilling Wonder Stories (collected in the book by the same title, 1973, Scholastic Book Services). This is an obscure short story from an obscure author that appeared in one of the lesser quality pulp magazines. It’s the story of a survey team returning from an exploration mission to an alien planet. The ship’s doctor believes that, while on the planet, one of the crew has been covertly replaced by some type of shape shifting alien life form. Initially, the alien has only the external form of the crewman but as time progresses it emulates human life more and more completely, down to the cellular and chemical level. The doctor has to devise a medical test to prove his theory to the captain in order to stop the ship from landing and releasing the alien into the Earth’s population. It’s a serviceable story and reasonably well written. The author clearly has little general scientific knowledge but focuses on medical science (Nourse was an MD, so this was his field). The other stories in the collection were similarly below the usual standard of 50’s science fiction and I don’t recommend the book.

The Duplicated Man by James Blish and Robert Lowndes, 1953, Columbia Publications. Horrible, horrible book. I found this almost unreadable (which is saying something for me – I love old badly written pulps most of the time!) Over half of this short book is a painfully slow setup of an overly complex political situation involving a war between Earth and an Earth colony located on Venus. Military officials on Earth run across Paul Danton, a political subversive who happens to look just like a Venusian official. They also dig up a weird human duplicating machine from the past and make five duplicates of Danton, all of which are randomly inaccurate copies. Confusion ensues. Not recommended.

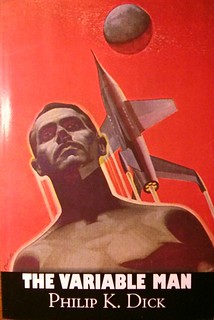

The Variable Man by Philip K. Dick, 1953, Space Science Fiction magazine (I’m reading the Aegypan Press book reprint). Cover art on the original magazine (and reprint) by Civiletti. Earth, in the year 2136, is surrounded by an alien stellar empire and unable to expand into the galaxy. Politicians determine Earth must go to war to survive. R&D labs work around the clock as government statistical computers calculate odds of Earth winning a war with each new weapon. When the odds are in Earth’s favor, war will be declared. Meanwhile, an Earth scientist testing a new FTL drive is killed in a spectacular failure, creating a huge explosion. Defense contractors realize the failed FTL drive is actually the ultimate weapon and plan to launch it into the primary star of the alien race. The computers evaluate their plan, leading to winning odds and a declaration of war. But, after the declaration of war, the researchers run into trouble duplicating the failed FTL experiment. Then an accident by a historical time research team results in an unknown variable – a fix-it man from the early 1900s has been dragged into the year 2136. The fix-it man has an unnatural ability to fix any machine, even machines of 2136. The odds computers break down, unable to calculate the effect of the new variable. The government wants him dead to eliminate his effects on the war effort. The defense contractor developing the FTL bomb wants him alive because he’s the only hope of fixing their weapon. One way or another he’ll determine Earth’s survival. Enjoyable and well-written. Recommended.

The Non-Statistical Man, Raymond F. Jones, 1956 (The book with the same title is 1964, Belmont Productions, Inc., B50-820, Cover art by Ralph Brillhart). At 80 pages, this is sometimes classed as a short story and other times as a novella. It was originally published in 1956 and then in a collection of four Jones stories found in this book by the same title. For a full review of the book, see my more in-depth review of The Non-Statistical Man. This short story is one of the most well-known science fiction treatments of the human characteristic of intuition. The title character, a statistician, is on the trail of potential insurance fraud when he stumbles onto what may be the next step in human evolution. By today’s standards the science is totally outdated and there’s a bit of sexism in the author’s stereotypical assumption that males are logical and females intuitive (though to be fair, the females turn out to be right so maybe it all balances out). The story is well written and still an enjoyable read. Recommended if you can find it.

The Reassembled Man by Herbert D. Kastle, 1964, Fawcett Publications. Cover art by Frank Frazetta. The most sexist, misogynistic book I’ve ever read. It was so bad I actually enjoyed it like a really awful movie. Edward Berner is a cowardly sexist jerk who is abducted by curious aliens. They offer Berner a deal. They want to disassemble his body down to the molecular level to study humans. If he’ll agree to let them do it, they’ll reassemble him with any improvements he wants. So he asks to be stronger, braver, and more intimidating. He wants a bigger penis and hypnotic-like sexual attractiveness to women. The rest of the book is a series of sexual exploits interspersed with visits to restaurants where he eats “manly” meals consisting of steak and large quantities of milk. There are frequent incidents of swaggering, fisticuffs, arm wrestling, strong arming, and a couple of gun and knife fights. He eventually dumps his long-suffering wife for a teen age girlfriend. Meanwhile, the aliens realize they’ve created a monster who might eventually ascend to control the Earth and return to fix their mistake. If you enjoy a really awful book, this is worth tracking down and reading.

The Transfinite Man by Colin Kapp, 1964, Berkley Medallion Books. Cover art uncredited, possible Paul Lehr. Ivan Dalroi is a private detective with a shady past who’s out to discover the secrets of Failway Terminal, a big corporate-owned building that serves as a sort of multiverse transit station. The corporation has a monopoly on transit so they essentially own entire universes full of real estate. Lots of political intrigue and action. The author has a strange obsession with “bogies” – those rotating wheel assemblies on the bottom of railroad cars. The hero is always jumping onto and off of railway car bogies (for never explained reasons trains are used to move between the alternate universes). The book provides a plot-twist ending similar to an old Twilight Zone episode. Readable if you run across it but a little below average and not worth seeking out.

The Unteleported Man by Philip K. Dick, 1964, Ace Books, Inc. (ACE DOUBLE G-602 cover art by Kelly Freas). This story was later expanded with 100 pages of additional material and released under the title “Lies, Inc.” but that version is not as well regarded as the original. It’s not a typical Dick story and not up to his usual standards. Rachmael ben Applebaum is the owner of a nearly bankrupt starship line. The other major lines are all gone and his will be next. The only place passengers want to go is a colony on the only known Earth-like planet. By the fastest faster-than-light starship the trip would be 18 years but with the new-fangled, monopoly-owned teleportation machine, the trip takes 15 minutes. The catch is that the trip is one way only and there is no faster-than-light method of communicating back to Earth. Once a colonist departs for the colony, they are never heard from again. Rachmael is convinced things are not as they seem. Maybe the UN is teleporting the excess population into non-existence or aliens are kidnapping the would-be colonists. Proving that there’s a conspiracy would also save his company, so he plans to take his fastest ship and become the first “unteleported man” to reach the colony and find out what’s really going on. But operatives of the teleportation firm are on to his plan and out to stop him from ever leaving the Earth. Below average for Dick but still readable and enjoyable.

The Artificial Man by L. P. Davies, 1968, Scholastic Book Services. Cover art is uncredited and, though a signature is visible, it’s unreadable. Davies is a British author whose novels bear similarities to those of American author Philip K. Dick in that they frequently deal with consciousness and reality. This novel is the story of Alan Fraser, a man who lives in a small English village in the year 1966. Fraser is a writer and is working on a science fiction novel set in the year 2016. The handful of others who live in the tiny village interact with him and often offer suggestions to help with his novel. Fraser begins to sense something odd about his life and begins to believe something is wrong with his reality. His friends seems to pop in and out of life as though their actions were scripted, the ideas they suggest to help him with his writing seem a bit too good. One day, while walking alone in the woods, he meets a girl from outside the village and both realize that something very strange is going on. She believes the year is 2016. Together they set out to discover whether Fraser’s world is real or an artificial construct. The book has a surprising number of similarities to the British Television series called The Prisoner. While I was less than satisfied with the ending, the book is very well written, very readable, and overall, very enjoyable. Recommended.

The Double Man by Eando Binder, 1971, Curtis Books, Modern Literary Editions Publishing Company, New York, NY. Cover art by Jack Faragasso. Like most stories by “Eando Binder” (the pseudonym for brothers Earl Binder and Otto Binder), this is a readable and moderately enjoyable, if unexceptional science fiction story. Wayne Durk returns to Earth after an experimental space flight to find that an exact double has taken his place. He has to work out who the double is and where he came from. Meanwhile, an alien virus is killing off the Earth’s best and brightest by targeting only humans with high IQs. Durk (and his double) are the two smartest scientists left and saving the world may depend on them working together. An enjoyable read and recommended if you happen to run into it but not worth seeking out.

The Aluminum Man by G.C. Edmondson

The Aluminum Man, by G. C. Edmondson, 1975. This one was written by an obscure science fiction author who was active in the 1960s through 1980s. Rudolf, a Native American Ivy League scholar, is taking a break from the world after publishing a novel. While on a canoe trip, he runs into a Flaherty, a perpetually drunk Irish metallurgist who is camped in the woods. In the same woods, the two of them meet a pregnant, shape-shifting alien, Tuchi, who desperately needs aluminum in order to get her ship off Earth before she gives birth to thousands of baby aliens. She has a bacterial process that produces aluminum but too slowly for her emergency needs. Against the advice of Flaherty, Tuchi and Rudolf make a trade; his aluminum canoe for the alien’s aluminum producing bacteria. Flaherty and Rudolf take the flask of bacteria and immediately head back to civilization with plans to make a fortune manufacturing aluminum. Tuchi discovers, as Flaherty predicted, that the aluminum in Rudolf’s canoe is not the pure element and is unusable. Feeling cheated, she sets out in search of the pair to exact her revenge. It’s unclear whether they’ll get rich, crash the world’s economy, or be killed by Tuchi first. The book is very much of a product of the 1970s with period slang and attitudes. But if that doesn’t bother you, it’s an enjoyable read and recommended.

The Female Man by Joanna Russ

The Female Man, by Joanna Russ, 1975. You wouldn’t expect a well-known example of feminist science fiction to turn up on this list, given the seemingly male theme, yet here it is. The Female Man deals with four women, or rather, four versions of the same women from four parallel Universes: Joanna, from our own Earth of the 1970s (she refers to herself as “the female man” to show her rejection of traditional gender roles); Jeannine, a hetrosexual librarian from an Earth where the Great Depression never ended; Janet, a lesbian from a post-apocalyptic Earth where only women survived a global plague; and Jael, an omni-sexual female assassin from an Earth where men and women live apart and on the verge of war. Janet’s world has developed technology that allows her to visit parallel Universes. She visits the worlds of Joanna and Jeannine (and takes them to visit each other’s worlds). Jael’s world has technology that allows her to observe other Universes and, during most of the book, she is merely an observer of the action. The book is a difficult read because it has no linear story or plot. The book shifts randomly (and frequently) between the points of view of the character’s four alter egos with no warning or explanation (and all of them refer to themselves as “the author”, “myself”, “I”). Most of the book is a series of vignettes concerning the character’s experiences, observations, or discussions of life in one of the other character’s Universes. There are occasional detailed lesbian sex scenes and frequent observations about gender roles, misogyny, and discrimination. In the last few chapters of the book there is a feeble attempt to introduce a plot: Jael is initiating a plan to secretly build up an army in an alternate Universe that she will use to exterminate the men of her world and she wants one of her three counterparts to volunteer their Earth as a base, leading each of the three to question their views of men. While I found the book neither enjoyable, nor an easy read, it was interesting and is probably worth reading just because of its historical value in feminist thought.

The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg, 1975 (I read the 1987 Warner Books edition with cover art by Don Dixon). This novel could be summarized as being a pessimistic, novel-length version of The Non-Statistical Man. That’s not quite true since The Non-Statistical Man involved insurance statistics while The Stochastic Man involves political polling projections. But the general idea is the same in that there is a man who seemingly has perfect insight into the future, allowing him to make perfect predictions where all normal statisticians fail. The biggest difference is that in The Non-Statistical Man, this is seen as a powerful tool that can bring about a better world if used properly, but in The Stochastic Man, it’s a terrible curse that leaves our protagonist seemingly helpless to stop a Trump-like authoritarian dictator from winning the US Presidential election and turning the future world of 2004 into a dystopia. If you don’t mind depressing books, then I suppose it’s recommended.

The Multiple Man, by Ben Bova, 1976. This book is intended as a suspenseful political thriller. Meric Albano is the President’s press secretary. He witnesses the secret service finding the dead body of a man who looks identical to the President. The dead man has the same fingerprints, same clothes, even the same DNA as the real president. Was it part of an attempt to assassinate and replace the president with an imposter? Could it be that the dead man is the real president? Are there other presidential duplicates around? When the Secret Service and the President conspire to cover things up, Albano must solve the mystery on his own before the plotters succeed at whatever it is they’re doing. The story takes place in the recent future as envisioned by Bova in 1976; a future that is now our historical past. So it feels like an alternate history at times, with outdated computer technology and political events that never happened in the real world. Even aside from those anachronisms, I kept experiencing a weird sense of deja vu throughout this book. It wasn’t the plot and I’m certain I never read the story before. About halfway through the book I finally realized why it seemed so familiar. It’s basically a Tom Swift Jr. book. It’s written on the same “young adult” reading level, and even has the same stock characters. Just as Tom Swift had Chow the chef, Albano has Hank Solomon as his amiable Texan sidekick (on computers – Hank Solomon: “How long d’yew think it’ll take th’ machine to figure things out?” Chow: “A good meal’d calm down ol’ think box but what do you feed that there contraption”). The writing style is so similar, I wouldn’t have been surprise if Tom Swift Jr. himself had shown up and saved the day by building a simple radio with his pocket soldering iron. Overall a reasonably enjoyable, if odd, read.

The Running Man, by Stephen King (writing as Richard Bachman), 1982. If you read the modern paperback with the introduction titled “The Importance of Being Bachman” by Stephen King, DO NOT read the introduction before you read the novel, it gives away the ending in detail. The Running Man is a dystopian science fiction novel of a future America in which wealth has become concentrated in the top one percent due to corporate control of politics. The only hope the average person has of getting ahead is to participate in the reality TV games, the ubiquitous form of entertainment produced by the Game Authority, aka “the network”. Ben Richards, facing unemployment and a sick daughter who will die if he can’t pay for her medical needs, decides the only hope for his family’s future is to enter the games. He walks to the huge Network Game Building and applies. His good physical condition, rare level of education, and tendency to question authority qualify him for the highest rated game of all, The Running Man. The game has no winners and is actually designed to eliminate undesirables from society but the participants receive 100 “new dollars” per hour of survival plus a one billion grand prize for surviving the full thirty days of the game (a prize that has never been claimed). Given a 12 hour head start, Richards can go anywhere, do anything, break any law, but he will have an army of private detectives and security forces hunting him as well as private citizens who receive prizes for turning in information about him. The novel follows Richards on his quest to survive long enough to save his daughter. The story line bears no similarity to the Arnold Schwartzenegger movie of the same name, except for the idea of a survival game. I enjoyed both the movie and the book despite the extreme differences. Recommended. It’s one of those books you won’t be able to put down once you start reading.

The Unincorporated Man, by Dani Kollin and Eytan Kollin, 2009. It’s long, at nearly 500 pages, and presents a dystopian world entirely based around an idea of economist Milton Friedman: everyone in the future is incorporated at birth. Their parents get 20%, the government gets 5%, the rest of the shares are traded on the open market. Your majority shareholders determine what education you receive, where you live, what career you must pursue, even your diet. The life goal of each person is to earn enough money to buy back a majority of their shares and gain some control over their lives. Into this world comes Justin Cord, a billionaire libertarian from the 21st century who cryogenically preserved himself when he learned he had cancer. He has prepared for almost everything, including hiding treasure troves around the world so that he can bring his wealth with him into the future. The one thing he was unprepared for was personal incorporation. To Cord, the idea amounts to slavery and he’ll have nothing to do with it. This sets him up for an ongoing fight with the world government and a much more powerful entity known as GCI, the corporation that controls cryogenic medicine and claims to own a share of Cord, since they found him and restored him to health. Cord must fight court battles, financial battles, assassination attempts, and political conspiracies along the way. Overall, I enjoyed the book and recommend it. The book is a first effort by the authors and shows signs here and there of inexperienced writing. The authors seem to have no clue about the hard sciences, so they rightly avoid them as much as possible and stick to things like economics and sociology. The few times the plots requires any science stuff, they borrow old ideas from 20th century futurists (e.g. “grey goo” from Eric Drexler) or prior science fiction. The book ends with a bit of a cliff-hanger, hoping to sell you on a series of three sequels. Unfortunately, reviews of the three following books seem uniformly bad, so I’m going to stop with this one.