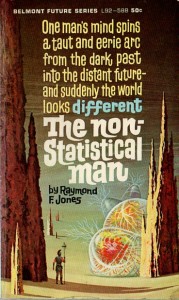

The Non-statistical Man is the story of Charles Bascomb, chief statistical analyst for a major insurance company; a man obsessed with logic and precision, a man who lives and breathes statistics, a man who endlessly ridicules his wife’s sense of intuition. His world slowly turns upside down after he discovers a series of anomalous insurance claims. Somehow a growing number of people are buying exactly the insurance they need, just in time to make a claim, and then cancelling. Convinced there is something possibly illegal and definitely strange going on, Bascomb sets out to investigate.

The trail leads to Dr. Magruder, an obvious quack who teaches self-help classes designed to develop the human sense intuition through a series of mental exercises and pills. The mental exercises are clearly nonsense and the pills turn out to be ordinary vitamins when analyzed. But somehow, where ever the doctor turns up, people begin outsmarting insurance companies. Every time Bascomb thinks he’s close to understanding the scam, logic and statistics fail him. His wife’s logic-defying intuition, however, repeatedly puts him back on the right track.

If Bascomb can’t put a stop to Magruder and his quackery, the entire insurance industry is doomed and field of statistics with it. In his desperation to preserve his world view and belief in statistics over intuition, Bascomb decides the only way to find out the doctor’s secret is to sign up for classes, take the pills, and follow the exercises. Strange doesn’t even begin to describe the events that follow.

The other stories in the book are enjoyable footnotes in SF history but don’t compare to The Non-statistical Man. The Gardener is the story of a child born with a mutation that gives him unusual mental powers. It’s notable primarily for an early use of the term Homo Superior. The term originated from Olaf Stapledon’s story Odd John in 1935.

The Moon is Death, set in a future of interplanetary travel, is the story of astronauts sent to Earth’s moon to find out why no mission there has ever returned. It reads like an early SF pulp story; you’ve got weird radiation, rapid aging, gun fights on rockets, and atomic explosions.

I found Intermission Time marginally more interesting. It involves colonists travelling to a planet with two intentionally designed societies that are experiments in solving problems that have plagued human history. Two musicians, a brother and sister, are destined for one of the colonies. John, the brother, falls in love with Lora, a woman he meets aboard the ship who’s destined for the other colony. Once a colonist commits to the voyage, they can’t back out or change plans and both colonies are sealed against contact with the other. The two lovers are faced with a series of dilemmas and choices, balancing individual relationships against the good of the species.

Lastly, I can’t help but add that this is the 1968 Belmont Future Series (B50-820) paperback edition published by Belmont Books of New York with some interesting and uncredited cover art by Ralph Brillhart done in his well-known style reminiscent of Robert M. Powers.